Mechanochemical activation of metallic lithium for the generation and application of organolithium compounds in air

Kondo Keisuke, Koji Kubota, and Hajime Ito

Beyond the limits of organic synthesis: ball mills open a new era

Organic chemists have long relied on solvents to carry out reactions, bringing molecules together in liquid media has been the backbone of the field. But what happens when a molecule won’t dissolve? That used to be a dead end. Now, a solvent-free method is breaking through those limits and capturing global attention.

Rethinking organic synthesis

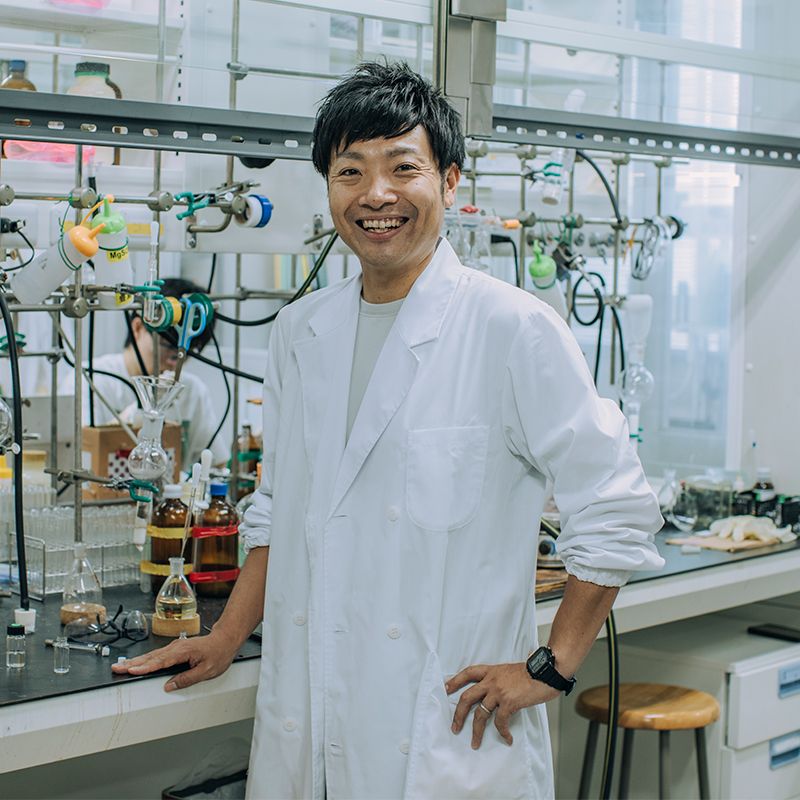

The Organoelement Research Laboratory at Hokkaido University is a recognized leader in organic synthesis research. As mechanochemistry gains traction internationally as a sustainable alternative to solvent-based synthesis, the team lead by Associate Professor Koji Kubota and Professor Hajime Ito has emerged as one of the global pioneers driving its application in organic chemistry. Their recent breakthroughs are challenging long-standing assumptions in the field.

“The conventional approach to synthesis in organic chemistry is like that”, explains Associate Professor Koji Kubota, “when you want to combine molecules A and B, you dissolve both into a liquid medium and make them bump into each other while controlling the conditions.” Solution-based synthesis is an actively developing research field, but it has a fundamental limitation – it only works with soluble components. The molecules that are insoluble are off the table; organic chemists have been accepting the status quo for decades.

In 2018, the Organoelement Research Laboratory broke with this convention and began exploring mechanochemical reactions using a type of grinding device called a ball mill. “It’s nothing complicated”, remarks Associate Professor Koji Kubota, “you put reactants and milling balls into a cylindrical container, then you need to shake it violently for the components to react”. The device is rotated horizontally at a frequency of around 30 Hz (30 times per second). The surprising result was that even without the use of a solvent the fine particles mixed uniformly, underwent changes in crystal structure, and reacted rapidly.

The reactants collide being in solid state, in the air. This surprisingly simple and reminiscent of a cooking process mechanochemical technique has enabled Professor Kubota and his team to achieve a series of key organic syntheses relevant to pharmaceuticals and functional materials, including the synthesis of organolithium compounds and cross-coupling reactions.

Towards efficient and sustainable production

Solvent-free mechanochemistry not only enables the use of otherwise insoluble components in the synthesis of new materials, but also drastically enhances reaction speed and efficiency. “If conventional solvents are like a spacious gymnasium, then a ball mill is more like a packed commuter train,” explains Kubota. As the volume of space decreased, the probability of molecular contact increased, resulting in a reaction rate approximately 400 times faster.

These efficiency gains also translate into major environmental benefits. Conventional pharmaceutical synthesis can produce up to 100 kg of waste per 1 kg of product—most of it solvent. Historically, these solvents were discarded in water, contributing to widespread industrial pollution. The shift to incineration, though safer, comes at the cost of high CO₂ emissions. In contrast, mechanochemical reactions have been shown to cut waste to 1/15 and CO₂ emissions to just 1/25 of traditional methods. As environmental regulations, particularly in Europe, continue to tighten, mechanochemistry stands out as a promising and practical solution for greener, low-impact manufacturing.

While ball mills are routinely used in the field of inorganic synthesis, for metals, ceramics, and other materials, applying them to organic chemistry was an unconventional move. “It was a risk,” says Kubota. “But if you want to pursue truly pioneering research, you have to cast your line where no one else is fishing.” Although trial uses of ball mills had been reported in the past, Ito Group was the first to clearly demonstrate the decisive advantages of mechanochemistry over traditional solution-based methods. “Breakthroughs often happen across the boundaries of the disciplines, and this was a textbook case.”

Paving the way to industrial application

Since publishing their first paper in 2019, mechanochemical organic synthesis has rapidly gained traction across academia, sparking interest among researchers from fields as diverse as polymer science, biology, and medicine, thanks in part to its intuitive, “easily explainable even to a high-school student” mechanism. It also generated interest from industry with Ito-Kubota team receiving inquiries from nearly 20 pharmaceutical and chemical companies.

To translate this growing interest into real-world application, in 2023 Professor Ito and Associate Professor Kubota established MechanoCross, Inc. (CEO: Tomohisa Saito), a Hokkaido University-certified startup, The company works to commercialize university’s patent on mechanochemical organic synthesis through technology transfer and collaborative development.

As the team moves toward industrial application, MechanoCross is collaborating with a plant machinery manufacturer to build the first full-scale reactor for mechanochemical synthesis, combining their chemical innovation with the mechanical engineering know-how needed for commercialization.

Through bold navigation across disciplinary boundaries, the Ito-Kubota team has cultivated unique expertise that opens new horizons where chemistry, mechanical engineering, and sustainability converge, placing them at the forefront of mechanochemical organic synthesis.

In parallel with their scientific breakthroughs, the Ito Group has also earned praise for its commitment to cultivating the next generation of researchers. Many of the lab’s alumni are now making significant contributions both in Japan and around the world. Kubota himself was a member of the lab’s first graduating cohort and now serves as both a role model and mentor to younger scientists.

He attributes the lab’s success to a student-centered philosophy: “We always put students first,” Kubota explains. Each student receives clearly defined individual goals along with personalized guidance, including support for daily habits and mindset. This rigorous yet supportive environment consistently produces individuals who are not only technically skilled, but also collaborative and trusted – “people who others want to work with.” His guiding principle is to help Hokkaido University students reach their full potential and become world-class researchers.

Faculty of Engineering, Division of Applied Chemistry

Associate Professor Koji Kubota